RADIC Educational Handbook - 3. Teaching and Learning

In this handbook, we use the definition of digital competence that follows the key competences for Lifelong Learning of the Council Recommendations in 2018 (Vuorikari et al., 2022).

“Digital competence involves the confident, critical and responsible use of, and engagement with, digital technologies for learning, at work, and for participation in society. It includes information and data literacy, communication and collaboration, media literacy, digital content creation (including programming), safety (including digital well-being and competences related to cybersecurity), intellectual property related questions, problem solving and critical thinking.” (Council Recommendation on Key Competences for Life-long Learning, 22 May 2018, ST 9009 2018 INIT).

This definition is integrated into our framework for Digital Rehabilitation Competences in East Africa. In the next section, we focus in on the teaching and learning process in this context. The use of e-learning environments in Digital Rehabilitation for adult learners requires an understanding of the unique characteristics and needs of adult learners. Therefore, we apply the basic principles of adult learning that should be considered when developing e-learning content and environments and supporting lifelong learning.

3.1 Learning methods to facilitate learners’ digital competences

Different learning approaches can facilitate learners’ digital competences. The philosophy of the learning and teaching methods are based on adult learning principles and support the lifelong learning (Collins, 2004). The fundamentals of adult learning methods accumulate and combine life experience and prior learning with new information. Adults are autonomous and self-directed. They are goal-oriented and active participants in the learning process. Learning is facilitated through collaborative, authentic problem-solving activities. Learning is enhanced when they create connections among participants. Adults learn more effectively when they receive timely and appropriate feedback and reinforcement of learning (Collins, 2004). The learning methods presented below were selected from the literature and based on the feedback from the needs of RADIC’s project partners. All the learning methods are based on these principles of adult learning.

3.1.1 Self-Directed Learning

To enable lifelong learning health professionals, need to manage their own learning by actively taking control of learning activities or self-directed learning. Based on social constructivist, and social cognitive learning theories, educational approaches should be used that emphasize the student’s active participation in learning, and develop knowledge and skills in the context in which they are applied (Van Lankveld et al., 2019). Learners must take responsibility for their own learning. E-learning platforms should provide opportunities for learners to set their own goals and choose their learning paths (Purnie, 2017).

In self-directed learning, learners initiate their own learning process, identifying what they need to learn and seeking resources and opportunities. Teachers encourage the learners to make decisions about their learning activities, timelines, and enhancing self-efficacy beliefs. Self-efficacy is highly relevant for learner self-regulation, or the degree to which learners are responsible participants in their own learning process (Van Lankveld et al., 2019). Self-efficacy could also refer to the learners’ confidence in his or her abilities to meet the challenges of Digital Rehabilitation.

Self-directed learning also encourages through intrinsic motivation, while focus in on interesting subject, personal growth continuing professional development (Dahal & Bhat, 2023). Feedback mechanism like self-assessments (see chapter 4) helps learners to understand their strength and areas of improvement.

3.1.2 Experiential learning

Experiential learning integrates real-world examples and experiential problem-solving activities into the learning process. By engaging learners in hands-on experience and reflection, they are better able to connect theories and knowledge learned in the classroom to real-world situations.

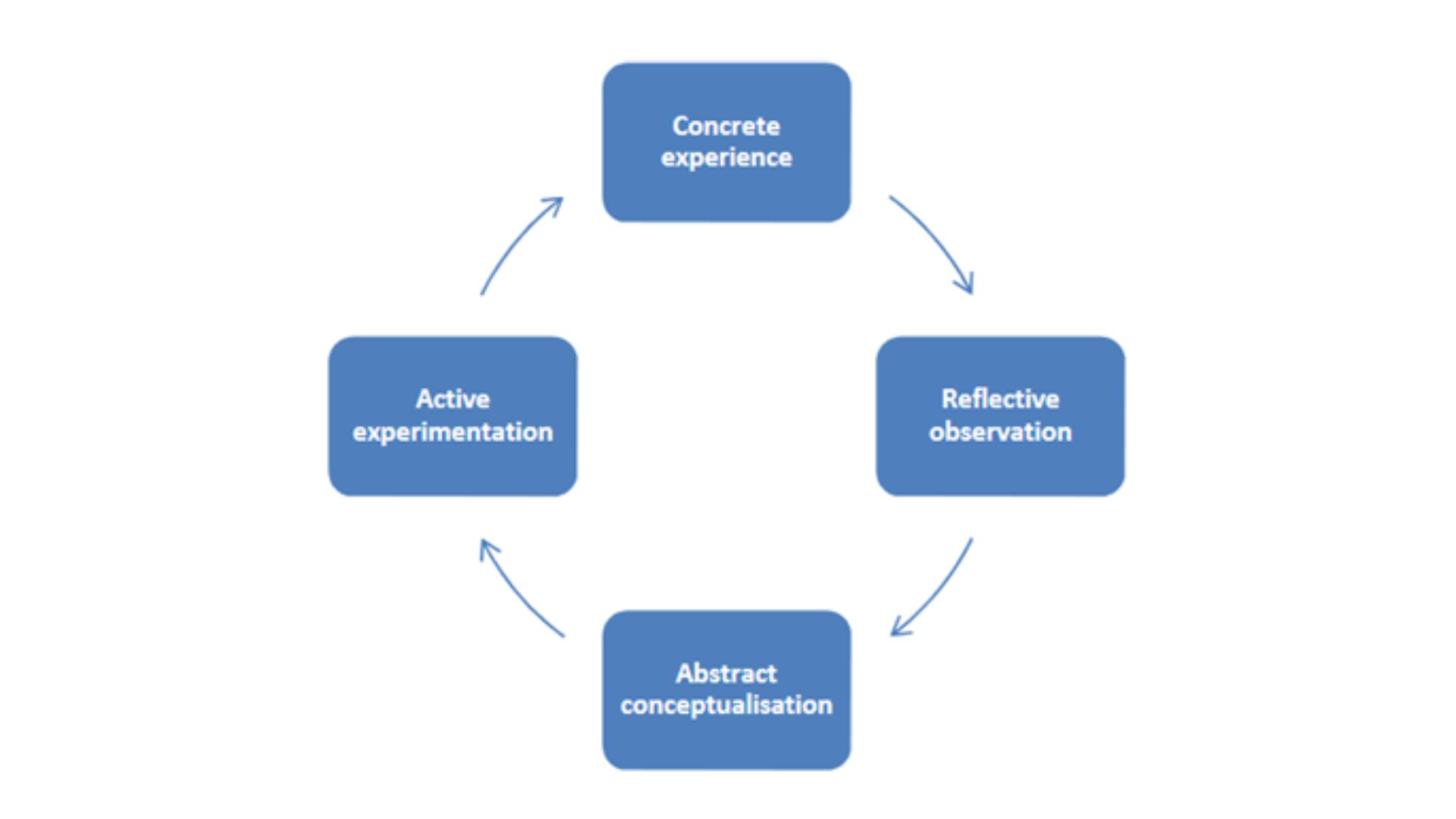

David Kolb described the ideal process of learning in a four-step Experiential Learning Cycle.

Learning takes place through [https://experientiallearninginstitute.org/what-is-experiential-learning/]:

- Experiencing (Concrete Experience): Learning begins when a learner uses senses and perceptions to engage in what is happening now.

- Reflecting (Reflective Observation): After the experience, a learner reflects on what happened and connects feelings with ideas about the experience.

- Thinking (Abstract Conceptualization): The learner engages in thinking to reach conclusions and form theories, concepts, or general principles that can be tested

- Acting (Active Experimentation): The learner tests the theory and applies what was learned to get feedback and create the next experience.

Each loop of the learning cycle shapes the next attempt at the task (see fig. 1). Teachers need to incorporate various interactive activities (e-activities) such as simulations and real-world examples, to build on learners’ previous experiences. This can empower learners to take charge of their own learning and development.

Figure 1. Kolb's learning cycle.

3.1.3 Problem-Centered Learning

A problem-centered learning approach built the knowledge through the students' active participation in the learning process. Problem-centered learning involves complex learning issues from real-world problems (cases) and makes that learner’s want to solve them. This makes the content is making relevant by using collaborative, authentic problem-solving activities and by linking theory to practice (Collins, 2004). The best-known approach is problem-based learning (PBL). PBL is a student-centered approach in which students learn about a subject by working in groups to solve an open-ended problem. This problem is what drives the motivation and the learning. PBL promote the development of critical thinking skills, problem-solving abilities, and communication skills (Yew & Goh, 2016). Read more in section 4.2.3.

3.1.4 Reflective Learning

Reflection is usually part of the learning process and has been identified as an important competency through Donald Schön’s book, the “Reflective Practitioner – How professionals think in action”. Reflective practice is the ability to reflect on one's actions in order to engage in a process of continuous learning. Reflection is an integral part of all learning methods. It can be seen explicitly how to encourage learners to engage in reflective practice, where they consider what they have learned, how they have learned, and how they can apply this knowledge in the future. Different models of reflection can help to deepen the learning process. Learn more in the reflection toolkit (https://libguides.cam.ac.uk/reflectivepracticetoolkit/models).

3.1.5 Collaborative Learning

Collaborative learning (CL) is an educational approach to teaching and learning that involves groups of learners working together in small groups to solve a problem, complete a task, or create a product. Different benefits are identified (Laal & Ghodsi, 2012):

1. Social benefits;

- CL helps to develop a social support system for learners;

- CL leads to build diversity understanding among students and staff;

- CL establishes a positive atmosphere for modelling and practicing cooperation, and;

- CL develops learning communities.

2. Psychological benefits;

- Student-centered instruction increases students' self-esteem;

- Cooperation reduces anxiety, and;

- CL develops positive attitudes towards teachers.

3. Academic benefits;

- CL Promotes critical thinking skills

- Involves students actively in the learning process

- Classroom results are improved

- Models’ appropriate student problem solving techniques

- Large lectures can be personalized

- CL is especially helpful in motivating students in specific curriculum

3.2 Teaching Methods

The following teaching methods integrate the elements of the learning methods described in chapter 3.1. It brings in different dimensions of the fundamentals of adult education and connects them with principles of lifelong learning. It also takes into account the landscape analysis of WP02 RADIC project and the curricula mapping of WP04 RADIC project, as well as the feedback from the project partners. There is no clear dividing line between the different learning methods. However, this is not the purpose of this manual. Rather, it is about identifying appropriate teaching methods for modules of Digital Rehabilitation.

3.2.1 Flipped Classroom

The Flipped Classroom is an educational approach that reverses the typical in-class and homework elements of a course. Preparratory materials are embedded in the Learning Management System (LMS). Students are first exposed to new material outside of class, usually through reading or videos. These materials facilitate pre-class learning and encourage active engagement, for example through problem solving or discussion during in-class activities (Baig & Yadegaridehkordi, 2023). These activities are supported by peers and teachers. The flipped classroom is a form of blended learning, which refers to any form of education that combines face-to-face instruction with computer-mediated activities.

The benefits of the flipped classroom show that students exposed to flipped classrooms developed better self-directed learning and critical thinking skills. It creates a more active and engaging learning environment by moving passive content learning out of the classroom and using class time for interactive activities. However, it also presents challenges, including the need for significant preparation, potential technological barriers, and varying levels of student readiness and motivation (Baig & Yadegaridehkordi, 2023).

Read more:

- https://docs.google.com/document/d/1arP1QAkSyVcxKYXgTJWCrJf02NdephTVGQltsw-S1fQ/pub#id.wdxrpadvxcrm

- https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/flipping-the-classroom/

- https://www.celt.iastate.edu/instructional-strategies/teaching-format/blended-learning-and-the-flipped-classroom/

- https://projects.iq.harvard.edu/flippingkit/more-resources

- https://www.adelaide.edu.au/flipped-classroom/the-flipped-classroom-explained

3.2.2 Case-Based Learning

The application of basic Digital Rehabilitation knowledge to specific client cases is a core element of rehabilitation, both as a discipline and as a practice. As a result, instructional approaches like case-based learning (CBL) have become essential components of many medical curricula, representing fundamental methods for educating future practitioners in their new profession. Despite the existence of various forms and didactic designs of CBL, a core element of this format is a teacher-guided discussion of a client case. During these discussions, students collaboratively apply learned principles and data analyses, evaluating the usefulness of various strategies to achieve optimal resolutions for the problems posed. This makes CBL a highly interactive seminar format in several respects.

First, an experienced educator guides students through a clinical case, activating their basic knowledge and engaging them in clinical reasoning processes, mainly through asking questions. These questions may clarify students' understanding of different phenomena, address the clinical management of specific clients, and consider the therapeutic consequences of diagnostic evidence (Gartmeier et al., 2019). Second, through their answers and the questions they pose themselves, students actively influence how a clinical case is discussed and analysed (Gade & Chari, 2013). Third, clinical educators also use peer-learning methods, such as small group discussions, as highly interactive didactic elements. During these periods, students form groups to discuss and make sense of the outcomes and consequences of diagnostic procedures (Irby, 1994).

Case-based learning has been shown to be effective in health professional education, as it fosters self-directed learning and the development of soft skills, such as communication and teamwork (Thistlethwaite et al., 2012). Additionally, the interactive nature of CBL supports teacher learning and improves student outcomes by promoting a deeper understanding through classroom discourse (Kiemer et al., 2014).

Read more:

- https://www.queensu.ca/ctl/resources/instructional-strategies/case-based-learning

- https://www.davinci-ed.com/resources/case-based-learning-cbl-in-the-online-classroom

- https://www.bu.edu/ctl/ctl_resource/case-based-learning/

3.2.3 Problem-Based Learning

Problem-Based Learning (PBL) is an educational approach that focuses learning through the active solution of real-world problems. It involves students working collaboratively in groups to determine the knowledge and skills needed to address a specific problem, thereby enhancing their critical thinking, problem-solving abilities, and self-directed learning skills. PBL scenarios are typically based on real-life situations, providing meaningful and relevant learning contexts.

The characteristics of PBL are a) the use of engaging tasks or authentic problems as a starting point for learning; b) self-directed learning: Students take responsibility for their learning, determining what they need to learn and seeking out resources independently; c) student-centered approach: Students take an active role in their learning process, often working collaboratively to explore and resolve issues; d) facilitative teaching role: Instructors serve as facilitators rather than traditional lecturers, guiding students' inquiry and supporting their learning process (De Andrade Gomes et al., 2024).

The success of PBL relies on its ability to foster self-directed learning habits, enhance problem-solving skills, and deepen disciplinary knowledge. In a typical PBL setting, learning is triggered by a problem that needs to be solved. PBL provides an instructional framework that supports active and group learning—based on the belief that effective learning occurs when students both construct and co-construct ideas through social interactions and self-directed learning. In an iterative process, students first engage in a problem analysis phase, then a period of self-directed learning phase and finally a reporting phase. A facilitator acts as a guide to scaffold students’ learning, particularly in the problem analysis and reporting components of the PBL tutorial (Yew & Goh, 2016).

Read more:

- Problem-Based Learning - Education - Maastricht University

- https://gsbs.uth.edu/files/faculty/Nilson%20Leading%20Effective%20Discussions.pdf

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xLqnxIR2Fj4

- https://teaching.cornell.edu/teaching-resources/engaging-students/problem-based-learning#:~:text=Problem%2Dbased%20learning%20(PBL),the%20motivation%20and%20the%20learning

3.2.4 Learning by Developing

Learning by Developing is an educational approach that integrates learning with real-world projects. This method aims to enhance student engagement, foster deep understanding, and develop practical skills. This method emphasizes collaboration, practical application, and the development of both subject-specific skills and broader competencies, such as problem-solving and teamwork (Raij, 2013; Tynjälä, 2008). Learning by Developing is built on five core principles: real-world relevance, collaboration, reflective practice, innovation and creativity, and sustainability. Projects are derived from actual industry or community needs, ensuring that students engage in meaningful and relevant work. Students, teachers, and external partners collaborate closely, creating a dynamic learning environment. Continuous reflection helps students integrate theory with practice and develop critical thinking skills. Students are encouraged to think creatively and innovatively to solve real-world problems. Projects are designed with long-term impact in mind, promoting sustainable solutions and practices (Raij, 2013; Tynjälä, 2008).

To effectively implement Learning by Developing, educators should focus on project selection, team formation, mentorship and support, reflection and assessment, and showcase and feedback. Choosing projects connected to students' fields of study with tangible outcomes, in collaboration with industry/external partners, is crucial (Raij, 2013; Tynjälä, 2008). The Learning by Developing approach offers several benefits: enhanced engagement, skill development, industry readiness, and lifelong learning. Students are more motivated and engaged when working on projects with real-world implications. The emphasis on reflective practice fosters a mindset of continuous learning and improvement (Raij, 2013; Tynjälä, 2008).

While Learning by Developing is beneficial, it also presents challenges such as being resource-intensive, assessment complexity, and student preparedness. It requires significant resources in terms of time, mentorship, and industry partnerships. Evaluating student performance can be challenging due to the diversity of projects and outcomes. Not all students may be ready for the self-directed nature of Learning by Developing; initial training and support are crucial (Raij, 2013; Tynjälä, 2008).

Read more:

3.2.5 Community-based Learning / Service Learning

Community-Based Learning (CBL) is an educational approach that combines community service with academic coursework, enhancing students' civic engagement and social responsibility. This approach offers a context for developing both academic and practical skills and is also known as service learning (Eyler & Giles, 1999; Bringle & Hatcher, 1996). Despite the diversity of definitions and theories related to CBL, some common characteristiscs exists (Flecky, 2011). Projects are designed to address real and pressing issues within the community. These projects engage students in research processes that address community issues. Students take the lead in planning and executing projects, with support from educators and community partners. Projects typically span weeks or months, allowing for deep interaction with community stakeholders (Flecky, 2011).

A strong partnership between educational institutions and community organizations is essential to the development of CBL programs (Eyler & Giles, 1999). Therefore, it is important to engage community stakeholders in the development process, seeking their input and expertise to ensure that the learning experiences are aligned with community goals and values. Evaluation and assessment play a dynamic role in the implementation of CBL. By integrating assessment methods that evaluate both student learning outcomes and community impact, program developers can increase the effectiveness and sustainability of CBL. This process creates a feedback loop that facilitates continuous improvement and refinement in the educational experiences provided (Bringle & Hatcher, 1996).

Read more:

- https://www.mightynetworks.com/resources/community-based-learning

- https://digitalservicelearning.eu/digital-service-learning-toolkit/

3.3 Co-Creation methods

Co-creation methods are collaborative approaches used by organizations to involve various stakeholders in the creation and development of products, services, or experiences. These methods aim to harness the collective creativity, knowledge, and expertise of participants to achieve better outcomes.

3.3.1 Carpe Diem Process

The Carpe Diem process in education is a dynamic and engaging approach that emphasizes active student participation, collaboration, and practical application of knowledge. Derived from the Latin phrase "seize the day," this method transforms classrooms into interactive spaces where students are active learners rather than passive recipients (Salmon, 2013). A key element of the Carpe Diem process is the active engagement of students, who take an active role in their learning through interactive activities such as group discussions, hands-on projects, and problem-solving exercises. Educators act as facilitators, guiding students and encouraging critical thinking and inquiry (Garrison & Vaughan, 2008).

Moreover, the approach values peer learning, with students working together, sharing ideas, and learning from each other. Educators create opportunities for group work and peer interaction to build a sense of community and enhance social skills (Boud, Cohen, & Sampson, 2014). Learning is contextualized with real-world examples, case studies, and scenarios, making it relevant and meaningful. Educators design lessons that bridge the gap between theory and practice, preparing students for real-world challenges (Kolb, 2014).

Continuous feedback and reflection are integral, helping students understand their progress and develop a growth mindset. Educators facilitate reflective practice by providing constructive feedback and encouraging self-assessment (Schon, 1987). The process leverages digital tools and online platforms to enhance learning experiences. Blended learning models combine face-to-face instruction with online activities for greater flexibility and accessibility (Graham, 2006).

By incorporating these elements, the Carpe Diem process empowers students, enhances their understanding and skills, and prepares them for future challenges. For educators, it represents an opportunity to create a vibrant and effective learning environment by seizing the day and transforming educational experiences.

Read more:

3.3.2 ABC learning design

ABC Learning Design is a contemporary pedagogical approach that emphasizes Activity, Background, and Collaboration as core components of the learning process. Developed by Young and Perović in 2016, this method aims to create a structured yet flexible framework that enhances student engagement, facilitates deeper understanding, and fosters collaborative learning environments. ABC Learning Design is particularly effective in higher education settings where the integration of technology and active learning strategies is crucial.

At the heart of ABC Learning Design is the focus on activity-based learning. This component emphasizes the importance of engaging students through hands-on, practical activities that promote active participation and experiential learning. Activities are designed to be interactive and dynamic, encouraging students to apply theoretical knowledge in practical scenarios. By incorporating activities such as problem-solving tasks, case studies, and simulations, educators can create a more stimulating and effective learning environment (Prince, 2004).

The Background component of ABC Learning Design focuses on providing students with the necessary context and foundational knowledge required to engage in higher-level thinking and complex problem-solving. This involves a combination of pre-class readings, multimedia resources, and introductory lectures that set the stage for more in-depth exploration during class activities. According to Bransford et al. (2000) providing a solid background helps students build a robust cognitive framework, enabling them to better understand and integrate new information. This preparatory phase ensures that students come to class ready to participate actively and meaningfully in the learning process.

Collaboration is the third pillar of ABC Learning Design, emphasizing the role of social learning and teamwork in education. Collaborative activities are designed to encourage peer-to-peer interaction, communication, and group problem-solving. By incorporating group projects, peer reviews, and collaborative discussions, educators can create a learning environment that mirrors real-world professional settings, where teamwork and communication are essential skills.

The benefits of ABC Learning Design are manifold. By integrating activity-based learning, students are more engaged and motivated, leading to improved retention and comprehension of material. The emphasis on providing a strong background ensures that students have the necessary context to engage in higher-order thinking and problem-solving. Moreover, the focus on collaboration helps students develop essential soft skills such as communication, teamwork, and critical thinking, which are highly valued in the modern workforce.

ABC Learning Design also presents challenges. One of the primary obstacles is the need for significant preparation and planning on the part of educators. Designing effective activities and ensuring that background materials are comprehensive and accessible can be time-consuming. Additionally, managing collaborative activities in a classroom setting requires skill and experience to ensure that all students participate actively and that group dynamics are positive and productive.

ABC Learning Design represents a forward-thinking approach to education that aligns with contemporary understanding of effective teaching and learning practices. By emphasizing activity, background, and collaboration, this method creates a rich, interactive learning environment that prepares students for the complexities of the modern world. As educational paradigms continue to evolve, methods like ABC Learning Design will play a crucial role in shaping the future of teaching and learning, ensuring that students are not only knowledgeable but also skilled and adaptable.

Read more:

Continue to the Chapter 4. Assessments >>

<< Back to the Chapter 2. Organizational and digital resources